Pakistan’s Gemstones, Minerals: An Overview

Pakistan is blessed with a diverse range of gemstones found in various regions of the country. Gemstone mining in Pakistan has been an important industry since ancient times, and the country is now recognized as one of the most significant producers of gemstones in the world. Here's an overview of some of the gemstones found in Pakistan:

Pakistan shares a long and porous border (2,430 km) with Afghanistan. This resulted in all kinds of Afghan minerals being dumped into Pakistan and traded from there. After the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, Pakistan's Northwest city of Peshawar became the first, direct and only market for all minerals found in the two countries. Prior to the occupation, Pakistan's only port city, Karachi, had the largest market in Pakistan (directional rough and precious stones only). With the rise of Peshawar, Karachi's importance and role in mineral resources was reduced to zero.

Mining and Business of Gemstones in Pakistan:

The mining and business of gemstones in Pakistan have a long and rich history, dating back to ancient times. Pakistan has been known for its precious and semi-precious stones for centuries, and gemstones have been a significant part of the country's economy.

The earliest records of gemstone mining in Pakistan date back to the Indus Valley Civilization (2600-1900 BCE). The region of modern-day Pakistan was rich in minerals and gemstones, and the ancient people of the Indus Valley were skilled in the extraction and trade of these precious commodities. The ancient city of Taxila, located in what is now Pakistan, was a hub for the trade of gemstones, and merchants from all over the world came to buy and sell precious stones there.

During the Mughal Empire (1526-1857), the mining and trade of gemstones in Pakistan reached new heights. The Mughals were great patrons of the arts, and they were particularly fond of gemstones. They brought skilled craftsmen from all over the world to work on their jewelry, and they commissioned some of the most exquisite pieces of jewelry ever created.

After the Mughal Empire, the mining and trade of gemstones in Pakistan continued to thrive. The British colonial authorities recognized the potential of Pakistan's gemstone resources, and they established a mining industry in the country in the 19th century. The mining of gemstones in Pakistan became more organized and professional, and the industry began to grow.

Today, Pakistan is one of the world's leading producers of gemstones, with a vast and diverse range of precious and semi-precious stones found in various regions of the country. The gemstone industry in Pakistan is a significant contributor to the country's economy, and the mining and trade of gemstones continue to be an important part of Pakistan's cultural heritage.

Mining Areas in Pakistan:

Pakistan has many mining areas that are rich in mineral specimens. Some of the most notable mining areas for mineral specimens in Pakistan are:

Minerals Occurrences:

Mineral occurrences in the Karakoram and Hindu Kush seem to be directly related to the mountain-building processes. The great variety in local country rocks, variations in element transfers along fault zones, differences in metamorphic alterations and geochemical conditions lead to the diversity of mineralization. Most of the minerals found in northern Pakistan come from pegmatites. Tourmaline, beryl (aquamarine) and apatite are good examples. Corundum and ben (emerald) owe then formation mainly metamorphic and hydrothermal processes. The processes of formation are not, however, always sharply defined.

Aquamarine and tourmaline tend to be relatively abundant in the young pegmatites in the High Himalaya. They are especially widely distributed in northern Pakistan, where they can reach majestic sizes and are often associate with apatite, topaz and garnet.

Yellowish brown to honey-yellow topaz are found in the pegmatites around Skardu. Rare pink to violet-red topaz comes from the Katlang region in the Mardan district, from calcite and quartz veins in carhonate rocks.

Pakistani emerald is arms mainly in the talc-carbonate schists of the Swat Valley and its western and eastern extensions. A wedge of these schists, part of the strongly deformed Tethys oceanic crust in the Indus- Yarlung-Tsangpo suture zone, is being pushed over the rocks of the Higher Himalaya along the Main Mantle Overthrust. The combined metamorphism of sedimentary and oceanic volcanic rocks, together with alteration by mineralized water, is likely responsible for the formation of emerald (Kazmi & Snee, 1989).

Pink to deep red ruby comes mainly from the metamorphic dolomite marble of the Hunza Valley and from the northern border of Pakistan, but is also known from the Neelum Valley in Azad Kashmir. The world famous cornflower blue sapphire from India-controlled Kashmir is found in strongly kaolinized pegmatite dikes, which are hosted in mica schists of the High Himalaya. This deposit is at elevations nearing 5,000 meters, but it seems to be exhausted.

Gilgit Baltistan:

The Baltistan region fall is in Pakistan's Northern Areas. The region is home to endless numbers of glaciers, rivers, and small, nameless streams. The best months to travel to Baltistan are August to October. It can get brutally hot in the summer with temperatures commonly reaching 44 degrees Celsius in the high mountains, d there is no shortage of blood-thirsty insect. Balti, a language not unlike Tibetan, is spoken in the region.

The northern reaches of Baltistan include some of the major peaks of the Karakoram along the Baltoro Glacier, making the region a magnet for extreme climbers. The 8,611. meter K2. also known as Mt. Godwin Austen. is the second highest mountain on Earth. K2. the adjacent Broad Peak (8,047 meters), Gasherbrum I (8,068 meters; also known as Hidden Peak) and Gasherbrum II (over 8.035 meters) are the highest mountains in the Karakorum Range. The 8.125-meter high Nanga Parbat (Naked Mountain) marks e northwestern-most corner of the Himalayas.

Austrian alpinists achieved first ascents of Nanga Parbat, Broad Peak and Gasherbrum II in the

1950s. It is somehow astonishing that the three mountains, traversed by hundreds of climbers, have not yielded much in the way of mineral specimens. In view of the rich material produced in the region, it seems strange that no beautiful specimens are known to occur either on K2 or on Gasherbrum. Georg Kandutsch once mentioned a slide-illustrated lecture given by extreme climbers on the ascent of Gasherbrum. On one slide Georg noticed, next to the posing climbers, two giant quartz crystals that reached from the ground to above the men's knees. When asked about the crystals, the climbers responded, "Yes, they were just laying around on the glacier, and we thought they would look nice on the photo, but we left them there "

While Afghan gemstones have been traded for millennila. the Karakoram Mountains have not been noted as significant mineral producers until the 20 century, with the lion's share of these specimens turning up after 1970, Italian scientists were among the first to make exhaustive studies of the geology and geography of the Karakoram Range, Ardito Desio's 1954 expedition to the Karakorams landed Italy the first ascent of K2 as well as a wealth of mineralogic, geologic, paleontologic and topographic data. The first ascent, a true team effort, was achieved by expedition members Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni on July 31,

Aquamarine From Gilgit Baltistan

The Route to Skardu:

Skardu is the capital of Baltistan. This city lies southeast of Gilgit at an elevation of around 2,300 meters. It takes a full day to drive the 215 kilometers from Gilgit to Skardu, and there are plenty of world-class mineral localities along the way.

The Gilgit-Skardu Road branches off from the Karakoram Highway about 37 kilometers south of Gilgit at the Alam Bridge. There the Indus turns north toward the Haramosh massif, famous for its finds of achroite, almandine, aquamarine, fluorite, clear quartz, diopside, ilmenite, epidote and recently green lazulite. Significant finds of magnetite, orthoclase, schorl, spessartine, titanite and topaz demonstrate the geologic diversity of this mineralogically rich region.

The at least 9-million-year-old Khaltaro pegmatites are first on a tour of the region's mineral-ogically important deposits. These pegmatites are significantly older than the other pegmatite

Microcline from Skardu Aquamarine From Skardu

Around Sassi:

Though not itself a mineral locality, the village Sassi is in the midst of a number of mineral destinations related to the Haramosh massif.

Six kilometers north-northeast of Sassi is the village of Dassu. This locality is very often referred to as Haramosh-Dassu so as not to be confused with Dassu in the Shigar Valley (or the Dasu south of Tormiq). The Haramosh-Dassu pegmatite is famous for producing superior, deep blue beryl, fine light brown topaz and in some cases schorl and fluorite. The locality has also been known to produce specimens of apatite, quartz and spessartine-almandine. I addition, Dassu has produced etched hydroxyl-herderite crystals associated with smoky quartz (Blauwet,

2003; Kazmi et al. 1985). It takes a minimum of one hour to travel the 6 kilometers to Haramosh-Dassu by Jeep. While the potentially fine minerals may be enticing, Pakistani dealers report that the prices for Haramosh-Dassu material are locally quite high, with a few dealers cornering the market for the relatively low production of intensely-colored stones.

Fine aquamarine and topaz have been discovered above Sassi, near the Ishkapul glacier. In the mid-1990s, Dudley Blauwet obtained a large cubic, pink fluorite with ilmenite said to have come from the locality.

Politically, Sassi, Haramosh-Dassu, and Khataro are all located within the Gilgit district, northern Areas. Specimens often come from Various vugs and veins that do not have specific, names, though most of the pegmatites in this general area are related to the NPHM. Even Pakistan, collectors are rarely buying from actual miners, who know precisely where a particular pocket is located. Specimens are thus often labeled "near Dassu," "Haramosh" or even less precisely "Gilgit."

In spite of the mineral riches surrounding Sassi, there are only a few dealers in town, and they trade low-quality material; nevertheless, Sassi is a nice place to stop along e dusty road for tea, fuel and local grapes, which are harvester in September.

Smoky Quartz Topaz From dassu, kohistan

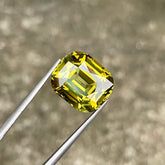

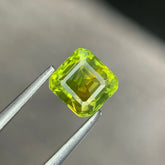

Pink Topaz from Katlang, Mardan:

The history of pink topaz from Katlang Valley dates back several centuries. Gemstone mining has been a traditional occupation in the region for generations, with local villagers using hand tools to extract gemstones from the earth.

Topaz was first discovered in the Katlang Valley in the late 19th century, with pink topaz being a particularly rare and prized variety. It was initially found by local miners who stumbled upon the gemstone while searching for other minerals and metals.

In the early 20th century, the British began to take an interest in the gemstones of the region, and mining operations became more formalized. The British set up mines and employed local workers to extract the gemstones, including pink topaz, from the earth. The gemstones were then exported to other parts of the world, where they were used in jewelry and other decorative items.

Today, pink topaz from Katlang Valley is still mined using traditional methods, with local villagers and small-scale mining companies working to extract the gemstones from the earth. The gemstones are still highly prized for their unique color and rarity, and are sold in markets around the world.

However, gemstone mining in the region is facing several challenges, including illegal mining, environmental degradation, and exploitation of local workers. Efforts are being made to address these issues and ensure that gemstone mining in the Katlang Valley is sustainable and ethical.

Pink topaz from katlang, Mardan

Picture by pinterest and minerals.net

Emerald from Swat:

The Swat Valley in northern Pakistan has been a significant source of emeralds for centuries. Emeralds from Swat have been highly valued for their unique color and transparency, and have been sought after by jewelry makers and collectors around the world.

The earliest recorded use of emeralds from Swat dates back to the 1st century AD, when they were traded along the ancient Silk Road. Swat emeralds were highly prized by the Mughal emperors of India, who used them in their jewelry and decorations.

During the colonial era, British explorers and gem traders began to take an interest in Swat emeralds. They recognized the quality of the stones and the potential for profit in the international market. In the early 20th century, mining operations began in earnest in Swat, with both local and foreign companies extracting emeralds from the area.

In the decades that followed, the demand for Swat emeralds continued to grow. However, political instability in Pakistan and the rise of conflict in the region led to a decline in mining operations. Today, Swat emeralds are still highly prized by collectors and jewelry makers, but their availability is limited due to the challenges of mining and exporting from the region.

Emerald From Swat Valley, KPK Province, Pakistan

Zagi Mountain: A Paradise for Rare Earth Mineral Collectors:

Zagi Mountain, also known as Zagi Shan, is located in the remote region of Pakistan near the border with Afghanistan. The area is known for its rich deposits of rare earth minerals, which are essential for a wide range of modern technologies, including smartphones, electric vehicles, and wind turbines.

The history of rare earth mining on Zagi Mountain can be traced back to the early 1990s when the first mining companies began exploring the area. Over the years, several large mining operations were established, and the region became a major supplier of rare earth minerals to the global market.

However, the mining activities on Zagi Mountain have been controversial due to environmental concerns and allegations of human rights abuses. In recent years, there have been reports of child labor and unsafe working conditions in some of the mines on Zagi Mountain, prompting calls for greater regulation and oversight of the industry.

Despite these challenges, the demand for rare earth minerals continues to grow, and Zagi Mountain remains an important source of these critical materials. The government of Pakistan has recently announced plans to develop the mining industry on Zagi Mountain further, with the aim of boosting the country's economy and creating jobs for local communities.

Quartz from Zagi Mounaitns., KPK Province, Pakistan

Summary of Pakistani gemstone mining areas

Pakistan is home to a wide range of precious and semi-precious gemstones, with several mining areas scattered throughout the country.

One of the most famous gemstone mining areas in Pakistan is the Swat Valley in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. The region is known for its emerald mines, which produce some of the highest-quality emeralds in the world. The mines in Swat Valley are primarily operated by local communities, who use traditional mining methods to extract the gemstones from the surrounding rocks.

Another important gemstone mining area in Pakistan is the Hunza Valley in the Gilgit-Baltistan region. This area is known for its deposits of various gemstones, including topaz, aquamarine, and tourmaline. The mines in Hunza Valley are mostly small-scale and operated by local communities.

In addition to the Swat and Hunza Valleys, other gemstone mining areas in Pakistan include the Kohistan region in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where ruby and spinel are found, and the Baltistan region in Gilgit-Baltistan, where sapphire and garnet are found.

Despite the potential for economic growth, the gemstone mining industry in Pakistan faces several challenges, such as political instability, lack of investment, and limited infrastructure. Efforts are being made to improve the situation, including the establishment of gemstone cutting and polishing facilities and the implementation of sustainable mining practices.

1 comment

Leave a comment

Please note, comments need to be approved before they are published.