Ikons, Classic, and Contemporary Masterpieces of Mineralogy

INTRODUCTION

The photos and text presented here are intended to provide a better understanding of a very esoteric and often mysterious subject: the collecting of world-class mineral specimens. This is an area of high exclusivity and high financial stakes, nearly inaccessible to most collectors. We hope to give a view here into that mystique. It has been our good fortune over the years to have known many of the world's top mineral collectors, and to have owned or handled many world-class specimens. Consequently, it seems appropriate to select examples from among those specimens to illustrate here, documenting for historical purposes the stories of how and where they were found, and the collections they have been a part of.

What makes a world-class specimen—one which, in simplest terms, is suitable for inclusion in the world's finest mineral collections? The question encompasses several categories based on distinctions that most collectors have probably not considered. Some specimens have an unforgettable visual presence, such that their images stay in the memory of the viewer. Some combine exceptional quality with important provenance and historical significance. Others, although collected too recently to be considered historical, are among the finest of their type. The common unifying factor is the exceptional quality of each piece, but the particular historical aspects and the flavor, so to speak, of their aesthetic impacts can also serve to categorize them in meaningful ways. To discuss these fine points requires terminology: We call the three main categories ikons, classics, and contemporary masterpieces, and will discuss them in more detail in the chapters that follow. All world-class specimens will fit into one of these categories and some may fit in two.

A brief discussion of the factors that determine quality, value and investment potential is followed by some practical suggestions for collectors who wish to personally build world-class collections. It's true that most readers of the Mineralogical Record may not have an opportunity to own such specimens. But then, neither will most of us ever have the opportunity to own a painting by Rembrandt, DaVinci or Van Gogh. Our inability to own them personally need not prevent us from appreciating them and learning all we can about them. On the contrary, world-class specimens are important, universally acknowledged focal points of study. In many ways, studying the Old Masters teaches us things about art that we could not hope to learn from lesser works, and so it is with the greatest mineral specimens— specimens that have achieved the pinnacle of development and perfection in ways only hinted at by lesser specimens.

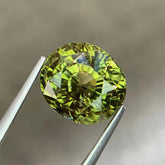

Picture by Minerals.net

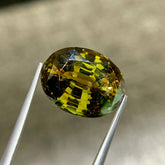

Picture by Minerals.net

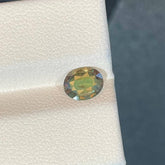

Showcase Put Together by The Collector's Edge for their 30th Anniversary

The Ultimate Guide To Categorizing World-class Specimens

IKONS

An ikon can be defined as the ultimate object of comparison. All mineral specimens of the same species, and often all mineral specimens of any species, are to be compared to ikons in discussions of quality, significance, impact and memorability. Ikons are aesthetically perfect in their own way. They have ' star quality; once seen, they are utterly unforgettable. Ikons may not possess the very largest crystals, and may not represent the very best colors, but there is something about them that is visually riveting, something that makes all collectors desire to possess them. Ikons achieve their lofty status purely on the basis of visual impact, with little or no consideration of provenance, history, or individual physical qualities. Examples exist in all fields. John Wayne may not have been the most handsome actor, or the most technically skillful in his acting, but he was undeniably a Hollywood ikon who may never be equaled in the public mind. The escalation in value that is typical of an ikon (like the pay scale commanded by Hollywood's top stars) is an excellent example of what collector Steve Smale has called the Van Gogh Effect. This effect operates when the value of a specimen spikes so rapidly and so high that it nearly defies logic.

Some examples will help to make this definition clear.

Tourmaline Blue-cap Tourmaline Queen mine,from Pala District, San Diego County, California

Beryl ( Aquamarine ) with Schorl from Shigar River Vallley, Skardu District, Northern Areas, Pakistan

Topaz with Quartz Shingus, from Skardu District, Northern Areas Pakistan

Tourmaline with Lepidolite from Pederneira mine, San Jose da Safira, Minas Gerais Brazil

CLASSIC

Classic is a term applied both to great minerals and to the localities that produced them, usually in the 19th or early 20th centuries. A classic mineral specimen is among the finest known representatives of its species-or at least it was so in its time. Classic localities (virtually all of them now extinct) exist throughout Europe, where mineral collecting got its start in the 16th century, but others are scattered around the world. True mineral classics are extremely collectible, are nearly impossible to obtain, and are among the best investments in the mineral world. The main reason why they are nearly unobtainable is that, like DaVinci paintings, the best ones were long ago acquired by the great museums of the world and are no longer in private hands.

Classic localities, as mentioned, are usually extinct - that is, worked out or inaccessible, with little or no chance of ever producing again. The specimens for which some classic localities are famous may have been challenged or bettered by newer discoveries, but their status as classics remains. For our purposes, a mineral specimen must be of the highest quality, the same quality that distinguished the best from the locality in its heyday, in order to be called a classic For example, although Kongsberg, Norway is a classic locality for wire silver, not every specimen of wire silver from Kongsberg ranks as a classic specimen - just the very best ones.

Bournonite from Herodsfoot mine, Cornwall, England

Silver from Kongsberg, Norway

Sulfur from Cozzodisi mine, Agrigento, Sicily, Italy

Epidote Knappenwand, Untersulzbachtal, Austria

Some examples of classic localities and their classic specimens include the following (among many others):

- Epidote from Knappenwand, Austria

- Manganite from Ilfeld,Germany

- Galena from Neudorf,Germany

- Silver from Freiberg,Germany

- Pyromorphite from Bad Ems,Germany

- Elbaite from the Island of Elba,Italy

- Sulfur from Agrigento,Sicily

- Azurite from Chessy,France

- Hematite 'roses' from Switzerland

- Pink fluorite from the Swiss Alps

- Bournonite from the Herodsfoot mine, Cornwall, England

- Barite from Frizington,England

- Stibnite from Ichinokawa, Japan

- Blue topaz from Mursinka, Ural Mountains,Russia

- Proustite from Chañarcillo,Chile

- Chalcocite from Bristol,Connecticut

- Wulfenite from the Red Cloud mine,Arizona

- Purple apatite from the Pulsifer quarry,Maine

- Leaf gold from Breckenridge, Colorado.

Classics are unlike ikons in that most collectors will not immediately be able to conjure up an image in their minds of Steve's particular specimens of these Classics, though all reasonably knowledgeable collectors are very familiar in general with the kinds of specimens that have come from these classic localities.

CONTEMPORARY MASTERPIECES

The term masterpiece is adopted here from the title of the book by Joel Bartsch and Wendell Wilson on the greatest minerals in the Houston Museum of Natural Science: Masterpieces of the Mineral World. Wilson and Bartsch, in turn, took the term from the permanent exhibit of great specimens in the Hillman Hall of Minerals and Gems in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, called the Masterpiece Gallery. They do not attempt to subdivide the Houston masterpieces on the basis of aesthetics, provenance, age or other factors.

The term masterpiece is a good one, implying the greatest work of a particular artist (in this case, the artist being Nature); a masterpiece is the work that elevated him or her to the rank of Master. In a sense, all world-class minerals are true masterpieces of Nature, of the Mineral World, as the Carnegie exhibit and the Houston book admirably demonstrate. But for our purposes here we need to specify those masterpieces that have been dug from the ground relatively recently and do not qualify as classics in the historical sense. Some people might call them

Contemporary Classics. If used at all, the term contemporary classics should be reserved for specimens produced relatively recently from occurrences that were classic, pre-World War II localities. Tsumeb dioptase would be one example: great specimens came out in the 1920's and 1930's, and again in the 1970's when the second oxidation zone was discovered.

I much prefer Contemporary Masterpieces as the designation for world-class specimens collected in the post-World War I era, from localities that were unknown as the source of great specimens before that time and which may or may not still be producing. Experience has shown that, although they are somewhat riskier investments than true historical classics, the very best specimens from post-war discoveries are hard to beat. The market value of these pieces may fluctuate somewhat if production continues, but buying the best almost always pays off in the end. Rhodochrosite from the N'chwaning mine in South Africa is a good example of a great mineral that experienced some volatility in price while specimens were actively being mined, but the finest specimens are now highly sought after and are worth many times the original selling price of 30 years ago.

Topaz from Ghundao Hill, Katlang, Mardan District Pakistan

Beryl ( Aquamarine ) with Fluorapatite from Chumar Bakhoor, Northern Areas, Pakistan

Beryl (Aquamarine) Blue mine, Shigar River Valley, Skardu District, Northern Areas, Pakistan

Beryllonite with Tourmaline from Paprok, Nuristan, Afghanistan

Leave a comment

Please note, comments need to be approved before they are published.